Many educated people take it as a given that the Exodus of the nation of Israel from Egypt, as described in the Bible, is simply a legend. After all, that’s the claim of prominent archaeologists working in Egypt and Palestine. For example, in 1999, Ze’ev Herzog, professor of archaeology (now retired) at Tel Aviv University, wrote in Haaretz:

[T]he Israelites were never in Egypt, did not wander in the desert, did not conquer the land in a military campaign and did not pass it on to the 12 tribes of Israel.

(“Deconstructing the Walls of Jericho,” Haaretz, Oct. 29, 1999)

This view is held by a great many dedicated, sincere researchers. Understandably, many thinking people take such assertions as fact.

However, even though the fictionality of the Exodus is taken for granted in mainstream academia and much of the educated public, this is not a universal view. I’ve recently come across a remarkably well-developed body of research that is worth considering by the thinking person.

However, even though the fictionality of the Exodus is taken for granted in mainstream academia and much of the educated public, this is not a universal view. I’ve recently come across a remarkably well-developed body of research that is worth considering by the thinking person.

American filmmaker Timothy P. Mahoney has put together an excellent film called Patterns of Evidence: Exodus, along with a book of the same name (I will reference here some page numbers from Mahoney’s book). I would strongly encourage open-minded people to see this film (the film is available at Netflix) and consider reading the book for much more detail (the book is available at Amazon in print and Kindle format).

The authenticity of the books of the Pentateuch (the first five books included in modern Bibles and attributed traditionally to Moses) is controversial for many reasons, often ideological. I care about the issue of the Bible’s authenticity, as it has religious implications. However, I’m also interested in the question as a writer of Biblical fiction. It’s possible to write the stories of The Edhai even if the literary sources are mythology. But if they are authentic history, that does add some weight to the stories themselves, as they then become historical fiction.

The evidence considered by Mahoney in his film and book is too extensive to consider entirely here. However, here are some points that I found salient and interesting:

Most mainstream researchers erroneously place the Exodus in the 13th century B.C.E.

Statue of Ramses II, Luxor., n.d., This slide colored by Joseph Hawkes. Goodyear. Brooklyn Museum Archives (S10.08 Luxor, image 9925).

Archaeological and historical researchers generally assume the year 1250 B.C.E. as the working date for the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. During that Late Bronze Age (LBA) period, they find no extra-Biblical evidence for an extensive Israelite presence in Egypt; or for a calamitous national collapse in Egypt; or for a massive departure of Israelite slaves from Egypt; or for a subsequent sudden destruction of Canaanite cities a few decades later, due to invading Israelites.

Researchers have traditionally focused on the 1250 B.C.E. date because this would place the Exodus during the reign of the powerful pharaoh Ramesses II, credited with the building of a city of that name. Exodus 1:11 says that the enslaved Israelites built a city called Raamses, so many researchers have asserted that the purported Exodus should be placed in the time period of Ramesses II. Mahoney calls this the Ramesses Exodus Theory (page 84).

However, Mahoney points out that Biblical chronology places the Exodus much earlier than 1250 B.C.E. His Chapter 8, “Challenging the Ramesses Exodus Theory,” (pages 189-217) presents multiple lines of evidence pointing to an Exodus two hundred years earlier, about 1450 B.C.E. Other researchers have argued for even earlier dates, such as 1513 B.C.E [see my article “When Did Moses (or Somebody) Write Genesis?“]

Fixing on the 1250 B.C.E. date for a purported Exodus means that archaeological researchers are going to be looking in the wrong time periods for a Semitic presence in Egypt, a sudden departure of a large slave population from the country, and a devastating invasion of Canaan forty years later. In fact, archaeological evidence for such events lines up much better with an earlier date for the Exodus. The connection of Ramesses II with the city mentioned in Ex 1:11 assumes that the name Raamses couldn’t have been used for the name of a city in earlier times. Insisting on such a connection seems unreasonable, especially considering the problems around the chronology of the ancient world and the fragmentary evidence it’s based on (see my article “Oxford scholar: Egyptian history is ‘a collection of rags and tatters.’”)

Archaeological and historical research reveal a large Semitic presence in Egypt during the Middle Bronze Age

The Biblical chronology would place the Israelites’ residence in Egypt during the Middle Bronze Age (MBA; conventionally dated as 2100-1550 B.C.E.), rather than the Late Bronze Age period proposed by the Ramesses Exodus Theory. Their departure would have been near the end of the MBA and beginning of the LBA.

In fact, archaeologists are currently uncovering an extensive Semitic presence in Egypt during the MBA. One of the important sites in this investigation is the ancient city of Avaris, which is being studied at Tell el-Dab’a in the eastern Nile Delta by an Austrian group led by Egyptologist Manfred Bietak. Mahoney visited the excavation and interviewed Bietak about it (see pages 87-92).

Map of Lower Egypt and the Nile Delta. The site of Avaris appears in the east delta. Jeff Dahl, CC BY-SA 3.0

The site covers about 2 square kilometers. It’s the same location where the ancient city of Ramesses is found, but Avaris is being uncovered at a lower (and thus earlier) level. Avaris is thought to have been occupied during the MBA from about 1850-1550 B.C.E. This would fit the Biblical chronology, which has the Israelites in Egypt from about 1728 to 1513 B.C.E., according to one well-known chronology.

Bietak said this to Mahoney about his findings at the Avaris excavation (pages 90-1):

We uncovered the remains of a huge town of 250 hectares with a population of approximately 25,000-30,000 individuals. These were people who have originated from Canaan, Syria-Palestine. Originally they may have come here as subjects of the Egyptian crown or with the blessing of the Egyptian crown. Obviously, this town enjoyed something like a special status, like a free zone, something like that.

Indications are that there are other such settlements of Asiatics from the same period in other areas of Egypt.

Mahoney asked Bietak whether the residents of Avaris could have been Israelites, but Bietak didn’t think so:

We have some evidence of shepherds. We find again and again in this area pits with goats and sheep. So we know shepherds, probably Bedouins, with huge herds roamed around this. But to connect this with the proto-Israelites is a very weak affair.

Why couldn’t these be the Israelites? Bietak responded:

According to my opinion, the settlement of the proto-Israelites in Canaan only happened from the 12th century BC onwards.

So Avaris is too early, according to the mainstream view, because of researchers’ ironic adherence to the Ramesses Exodus Theory.

Mahoney presents other interesting findings in his film and book, some more compelling than others. One of the more fascinating findings is a document called the Brooklyn Papyrus, a Middle Kingdom Egyptian papyrus that includes a list of slave names from an estate in southern Egypt (pages 161-3). According to independent scholar David Rohl, 70 percent of the names are Semitic, including some names that actually appear in the Bible, such as Menahem, Issachar, Asher, and Shiphrah — not necessarily the same people from the Bible, but people with the same names.

So why is the list of slave names in the Brooklyn Papyrus not taken by mainstream researchers as supporting evidence for the Israelite sojourn in Egypt? You guessed it: This evidence doesn’t fit the mainstream view that any Israelite presence in Egypt belongs to a later period. The papyrus belongs to the Middle Kingdom, conventionally dated about 2000-1700 B.C.E., associated with the 11th to 13th dynasties.

Rohl told Mahoney (page 163):

Although everybody recognizes that this is a list of Semitic slaves, and everybody recognizes the names appearing in the list are also Israelite names, these can’t be the Israelites, because it’s the wrong time period. The Israelites are [supposedly] much later in history. So these people we’re seeing here in the Brooklyn Papyrus cannot be the Israelites …

So scholars put the text to one side and say it’s another coincidence.

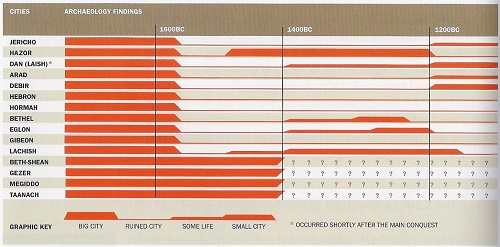

Archaeologists do not find evidence of the sudden destruction of key Canaanite Cities ca. 1200 B.C.E., but there is evidence of an earlier destruction

Many prominent archaeological researchers working in Palestine assert that there is no evidence for the kind of invasion described in the book of Joshua. Some even claim that the Israelites were just a group of Canaanites who emerged from the general population and invented a pious fiction to justify their rulership in the Holy Land.

Israel Finkelstein, professor of archaeology at Tel Aviv University, told Mahoney in an interview (pages 232-3):

First and foremost, many places which are mentioned in Joshua in the Conquest story, specifically mentioned as major places in Canaan, were excavated, and no evidence for a city in the Late Bronze Age has ever been found. And I’m speaking about major excavations. And we are speaking about many sites. It’s systemic; it’s not only a single site. Take the example of Jericho. In Jericho there is no big city the in the 13th century B.C., okay, any way you look at it.

By now, it should jump out at you that Finkelstein is assuming the same 1250 B.C.E. Exodus date common among mainstream researchers, with the purported Conquest coming 40 years later. Paradoxically, many of these same researchers claim that the Exodus story is a legend anyway, so a thinking person might wonder what the point is in relying on the 1250 Ramesses date for an event that supposedly never occurred.

Anyway, some of the minority researchers consulted by Mahoney make the point that there is in fact evidence for the destruction of a number of key Conquest cities much earlier, including Jericho and Hazor.

Archaeological findings suggest that a number of key Canaanite cities were destroyed around the end of the Middle Bronze Age, about 1550 BCE. From Patterns of Evidence: The Exodus, page 252.

John Bimson, professor of Biblical studies at Trinity College Bristol, tells Mahoney that there is a pattern of destruction of Canaanite cities at the end of the Middle Bronze Age, conventionally dated at 1550 B.C.E. This includes many cities specifically mentioned in the Bible’s Conquest account. Bimson says (page 253):

We know that cities like Jericho and Hazor were major cities at that time, and in both of those cases, those cities were destroyed by fire, as the Bible describes. So if we go to this earlier date, we have a very good fit with a whole list of sites, a good fit between the biblical narrative and the archaeological evidence.

A wrinkle: The conventional chronology for Egypt is problematic.

Conventional chronology of ancient Egypt, compared to a revised chronology by David Rohl. via Wikimedia. Click to see the image in full size.

Some sincere researchers are critical of the conventional timeline ascribed to ancient Egypt, which has been standardized for many years and has become an important anchor for the proposed chronologies of other Near East civilizations, including Canaan. Critics have asserted that the Egyptian chronology has been over-inflated, for example, with regard to the Third Intermediate Period, conventionally dated 1069-664 B.C.E.

Mahoney writes (page 272):

[I]t’s been necessary to artificially insert dark periods into the timelines of all the surrounding civilizations, so that they match the dates of Egypt’s Third Intermediate Period. Yet some scholars maintain that the archaeology of these cultures does not seem to support such dark periods. They believe something is wrong.

Bimson tells Mahoney:

The 18th, 19th, and 20th Dynasties are dated too early because the Third Intermediate Period is too long.

Understandably, trying to readjust the timeline would not be a welcome effort among historians and archaeologists who have spent their careers assuming the standard chronology. Certainly, mainstream researchers feel they have solid reasons for not re-examining such assumptions. But the thinking person might keep in mind how hard it is to reconstruct civilizations and events that occurred three or four thousand years ago.

As Egyptologist Alan Henderson Gardiner wrote in 1966:

Even when full use has been made of the king-lists and of such subsidiary sources as have survived, the indispensable dynastic framework of Egyptian history shows lamentable gaps and many a doubtful attribution. If this be true of the skeleton, how much more is it of the flesh and blood with which we could wish it covered. Historical inscriptions of any considerable length are as rare as the isolated islets in an imperfectly charted ocean. The importance of many of the kings can be guessed at merely from the number of stelae or scarabs that bear their names. It must never be forgotten that we are dealing with a civilization thousands of years old and one of which only tiny remnants have survived. What is proudly advertised as Egyptian history is merely a collection of rags and tatters.

The tentative and fragmentary reconstruction of the past carried out by researchers, however well-intentioned and hard-working, doesn’t necessarily justify disregarding the historical accounts in the Bible.

These are actually only a few of the fascinating points raised by Mahoney in urging a reconsideration of the evidence for the Exodus of Israel from Egypt in ancient times. For thinking people with an open mind about ancient history, I highly recommend viewing Timothy Mahoney’s film, Patterns of Evidence: Exodus, and reading his book of the same title.

ARK — 2 April 2016