The short answer is no, but he has said some interesting things about who God might be.

This question came to my attention this past week, when someone pointed me to articles on this topic, including “Top scientist claims proof that God exists, says humans live in a ‘world made by rules created by an intelligence’,” at the website Christian Today. That article makes the claim:

A respected figure in the scientific community recently said he found evidence proving that there is a Higher Being, which he described as the action of a force “that governs everything.”

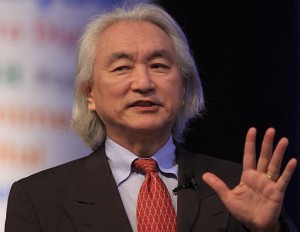

Theoretical physicist Michio Kaku, who is known as one of the developers of the revolutionary String Theory, said theoretical particles known as “primitive semi-radius tachyons” may be used to prove the existence of God.

However, nothing on this topic appears on Kaku’s official website, and a search of academic sources reveals nothing written by Kaku referring to “semi-radius tachyons.” According to Jay L. Wile, a nuclear chemist and textbook author,

Tachyons are theoretical particles. We have no idea whether or not they exist. If they exist, they travel faster than the speed of light, so it’s hard to know how in the world we could ever detect them, much less conduct tests on them. I have no idea how such particles can tell us something about the nature of the universe. I looked in vain for an article on the subject authored by Dr. Kaku himself. I then went to his Facebook page, which made no mention of this “monumental discovery.”

Since I couldn’t find anything written by Dr. Kaku, I decided to investigate these “primitive semi-radius tachyons” myself. I had never heard that term before, but then again, I am not a particle physicist. So today, I tried to find the term in my reference books. I could not. When I did an internet search on the term, the only hits I got were to articles about this supposed discovery. As a result, I seriously doubt that primitive semi-radius tachyons exist, even in the minds of theoretical physicists.

Wile, in fact, discovered that this assertion about Kaku’s “discovery” goes back to at least 2013, when it was apparently circulating on Spanish- and Portuguese-language websites.

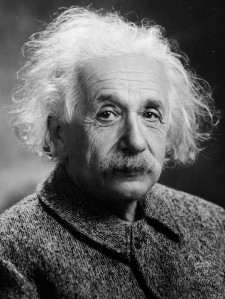

So the claims that Michio Kaku has found God seem fabricated, or at least exaggerated. However, I do find that Kaku has made some interesting statements about the possibility of design in the universe. Wile characterizes Kaku as “a theoretical physicist who had done some cutting edge research a couple of decades ago, but is more of a ‘scilebrity’ today, promoting science and his ideas about the future on television shows, etc.” For that reason, it’s possible to find a number of video presentations by him. In some ways, Kaku seems to espouse a belief in the god of Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza, who believed not in a personal God, but in a god “who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists,” as Albert Einstein put it.

In a 2013 video program, Kaku said:

The goal of physics, we believe, is to find an equation perhaps no more than one inch long, which will allow us to unify all the forces of nature and allow us to read the mind of God.

And what is the key to that one-inch equation? Super-symmetry. A symmetry that comes out of physics, not mathematics, and has shocked the world of mathematics.

But you see, all this is pure mathematics, and so the final resolution could be that God is a mathematician. And when you read the mind of God, we actually have a candidate for the mind of God. The mind of God, we believe, is cosmic music, the music of strings resonating through eleven-dimensional hyperspace. That is the mind of God.

And in a 2011 interview, he more specifically referenced Einstein and Spinoza:

Einstein was asked the big question, Is there a God? Is there a meaning to everything, right? And here’s how Einstein answered the question. He said there really are two kinds of gods. We have to be very scientific. We have to define what we mean by God. If God is the God of intervention, a personal God, a god of prayer, the God who parts the waters, then he had a hard time believing in that. Would God listen to all our prayers, for a bicycle for Christmas? Smite the Philistines for me, please.

He didn’t think so. However, he believed in the God of order, harmony, beauty, simplicity, and elegance, the God of Spinoza. That’s the God that he believed in, because he thought the universe was so gorgeous. It didn’t have to be that way. It could have been chaotic. It could have been ugly, messy. But here we have the fact that all the equations of physics can be placed on a simple sheet of paper. Einstein’s equation is only one inch long. And the quantum theory is about a yard long, but you can squeeze it onto a sheet of paper…

… And with string theory, you can even put those two equations together, and string theory can be squeezed into an equation one inch long. And that equation, but the way, is my equation. That’s String Field Theory. That’s my contribution.

But we want to know, where did that equation come from, you know. This is what Einstein asked. Did God have a choice? Was there any choice in building a universe? When he woke up in the morning, he would say, “I want to create a universe. I want to be God today. What kind of universe would I create?” This is how he created much of his theory.

So, Kaku doesn’t really claim to have proven the existence of God through physics. However, he does acknowledge that the physical universe implies that there is something more going on than just a big random mess.

ARK — 19 June 2016